Stephen Schmidt

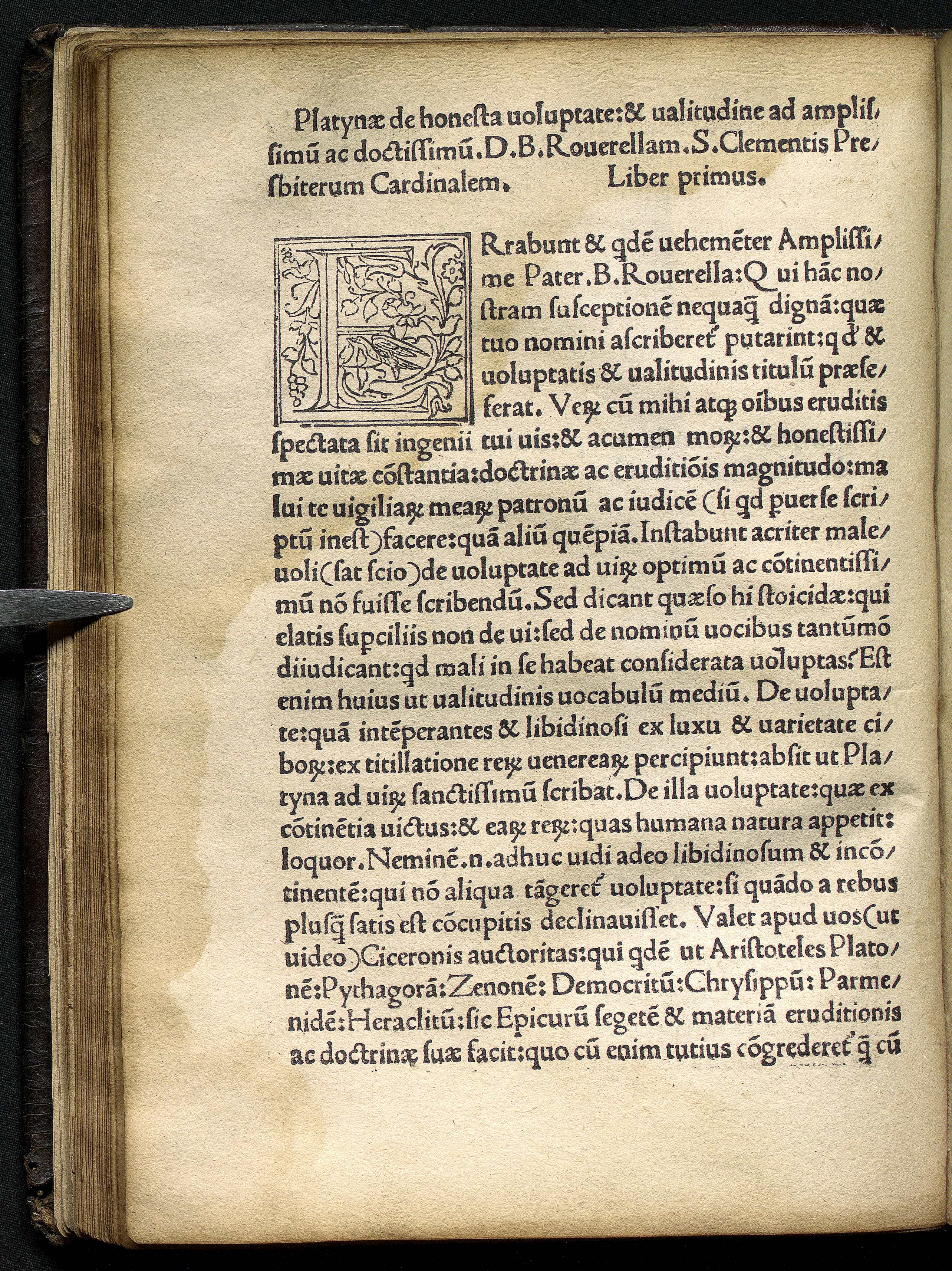

The modern Anglo-American tradition of manuscript cookbooks might be said to begin with the world’s first printed cookbook, De honesta voluptate et valetudine, or “On right pleasure and good health,” as the title is conventionally translated from the Latin. Authored by the celebrated humanist writer Bartolomeo Sacchi, known as Platina, and first published, in Rome, around 1474, the book was translated into Italian, French, and German within a few decades of publication, and it remained widely read throughout Europe into the early eighteenth century. The book featured both a new cuisine and, just as importantly, a new attitude toward food and  cooking. Platina presented an interest in food and its preparation as a kind of connoisseurship akin to the connoisseurship of painting, music, or literature—another gilded arrow in the quiver of the man of virtù. Europe came to call Platina’s attitude toward food and cooking “epicurean,” and those who espoused it “epicures.” Today, we take such individuals for granted—we call them gourmets, or perhaps foodies—but at the dawn of the sixteenth century, they were new individuals, emblematic of the Renaissance European world.

cooking. Platina presented an interest in food and its preparation as a kind of connoisseurship akin to the connoisseurship of painting, music, or literature—another gilded arrow in the quiver of the man of virtù. Europe came to call Platina’s attitude toward food and cooking “epicurean,” and those who espoused it “epicures.” Today, we take such individuals for granted—we call them gourmets, or perhaps foodies—but at the dawn of the sixteenth century, they were new individuals, emblematic of the Renaissance European world.

In the sixteenth century, when Renaissance Italian epicureanism was first unleashed in Europe, England was in the throes of a cultural and intellectual renaissance, which is usually dated from the accession of the Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch, in 1485, through the end of the reign of James I, the first Stuart king, in 1625. In England, as elsewhere in Europe, the Renaissance was characterized by a skepticism toward the received wisdom of the Middle Ages and a striving for fresh knowledge about the world, gained through observation and experiment. Among the English elite classes, one of the ways in which this quest for new knowledge found expression was the collecting and creating of recipes, known then, and well into the nineteenth century, by the now-archaic word “receipts.” Originally, the word receipt meant a prescription for a medicine or remedy. During the Renaissance, as the knowledge-hungry English began to write and collect prescription-like formulas for all sorts of things, receipt broadened to denote virtually all of them: directions for farming and building; formulas for chemistry and alchemy; recipes for practical household products like cleaning solutions and paints, and, amid the growing epicurean spirt of the time, food recipes. To a modern way of thinking, these various receipts would logically be collected in separate receipt books according to their subject matter. However, the distinction made by the sixteenth-century English was between receipts pertaining to the home and commonly undertaken by women, and receipts for things involving work outside the home, which was assumed to be generally the concern of men. Thus, most of those who collected food and drink recipes also collected in the same books receipts for medicines, remedies, cosmetics, and household necessities like candles, cleaners, pesticides, fabric dyes, and ink, all of which were commonly made in the home, either by or under the supervision of the lady of house. Today, these books of mixed home recipes are often referred to as “cookbooks” when a substantial portion of their recipes concern food and drink.